Fashion professor honors Kent State alum in the wearing justice exhibition

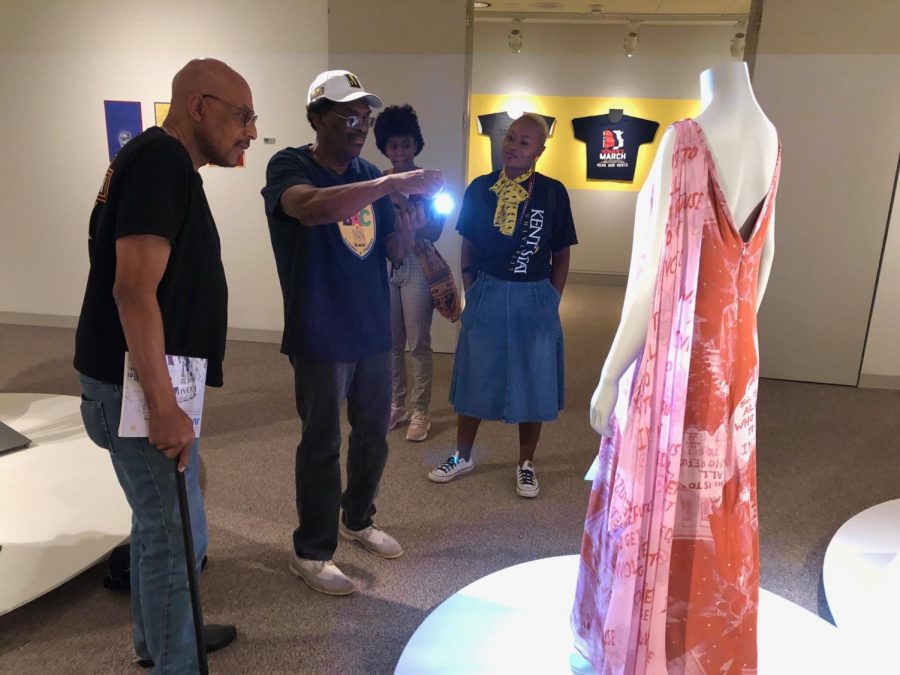

Silas Ashley takes a photo of the dress associate professor Dr. Tameka Ellington created. Ellington created the dress from a 1972 photo of Ashley protesting the Vietnam War.

October 2, 2019

When associate fashion design professor Tameka Ellington decided to design a dress for the Kent State Museum’s Wearing Justice exhibition, she wanted to pay homage to the protestors of Black United Students (BUS) that led a demonstration against the Vietnam war in 1972.

Ellington honored them by designing a dress that has the face of Kent State alum and former president of BUS, Silas Ashley.

The dress is featured in the Wearing Justice Exhibition and called, “This is to All Who Refused Involved!: The Vortex of Black Protest Propaganda.”

Ellington said the garment “signals a renewed identity and purpose for blacks” and dedicated the piece to all black people in the African diaspora.

The garment is an inspired Vogue pattern by fashion designer and fashion school founder Jerry Silverman and features an image of Ashley who is the current president of the black alumni chapter, which currently “serves over eleven thousand alumni living in the United States.”

Ashley and members of BUS gathered outside of Rockwell Hall in April 1972, with tombstones they had created. Each tombstone had a message and represented the lives of soldiers that were lost due to the Vietnam war.

Ashley’s tombstone read: “This to all who refuse to get involved.”

The protests were part of demonstrations that took place after the National Guard fired their rifles at Kent State students who were protesting the Vietnam War on campus on May 4, 1970, killing four and wounding nine.

“The tombstone he was standing next to really struck me because when I think about black people and black protests, and the fact that we have been protesting for our human rights for so many years,” Ellington said. “But there’s still so many of us who are not living up to our potential.”

The photo of Ashley on the dress was taken by emeritus professor Edmund Timothy Moore.

“As I was looking at the photo, I was like, he’s in front of Rockwell and because I’m a fashion student that for me, was very personal because this is where I got my education,” Ellington said. In the 70s, Rockwell Hall held the president’s office.

A year before the May 4 shootings, Ashley was a freshman at Kent State in 1969, where he majored in political science and minored in history. He lived in Dunbar Hall and described the university as being segregated as to where there weren’t many extracurricular activities for black students.

“We had to fight for everything we got and therefore we were constantly involved in terms of combativeness with the university structure,”Ashley said.“Just trying to get our basic rights.”

Ashley said, his freshman year ended on May 4 because of the shootings and described it as an experience that should not be repeated. He recalls there were ramifications that followed after that day because if a student didn’t get enough credits during the school year there was a chance they could have been put in the draft and sent to Vietnam.

“As a student, I learned a lot about life. I’m out of Cleveland, fresh out of high school and I see all of these things happening that I was not familiar with in terms of the anti war, overt racism even interacting with whites,” Ashley said.

After the events from his youth, seeing his face on Ellington’s garment in the Wearing Justice Exhibition, he called it one of the greatest moments of his life.

“It’s something that I will forever be grateful that she felt that much to do something like that,” Ashley said. “And this will always be home in spite of everything that happened here. This will always be home because of that.”

Ellington said, out of all the experiences she has had in her life, she described this one as amazing because these were students who made it possible for other blacks students to be a part of Kent Sate’s campus.

“At one point, black students were not even allowed to live on campus,” Ellington said. “They had to live (in) other places, and me being able to honor what those students did before I became a student there, it’s amazing.”

Contact Gershon Herrell [email protected].