OPINION: Professors, it’s time to rethink that mandatory cameras-on policy

March 4, 2021

I know, I know. Professors who adopt cameras-on policies for their online classes are usually well-intentioned.

They want to make sure we’re understanding the material and engaged. They want to give us a sense of connectedness and community during an isolating pandemic. They say they teach better when they’re not lecturing to blank screens. And they argue that, with many companies forecasting their employees will work remotely long-term or even permanently, we might as well get practice teleconferencing now.

I am the last person who would deny that learning with my camera on has its benefits. I know how I learn best: mic on because I’m a verbal processor. Video on because my mind wanders far and often otherwise. Emoji hand raised a couple of times per class because I want professors to know my name and research interests so they can (among other things) vouch for me when it comes time to find a job.

But I am also a student who has a quiet space to work, family members who respect my privacy and the income to pay for a stable internet connection and hardware that supports Zoom backgrounds. I recognize being easily able to turn my camera on is not a privilege all students have.

In fact, in a KentWired Instagram and Twitter poll, 60 percent of respondents said they are in a situation that makes it difficult to turn on their cameras for classes. And 68 percent said they share a work environment with more than one person.

In the same poll, 71 percent of respondents said they felt it was unfair for professors to require students to have their cameras on. A mere 27 percent said they felt they learned better with their camera on. If administrators trust students’ perceptions of their circumstances enough to allow them to take out huge amounts of student loan debt, we should also trust their perceptions of their learning environment.

Because of this, I question if the benefits of a mandatory cameras-on policy outweigh the potential harm it could do, especially to students from low-income families or students living with a mental illness or disability. Moreover, I question what example it sets for young professionals preparing to enter fields like medicine, law, engineering and journalism where the ethical standard is “do no harm.”

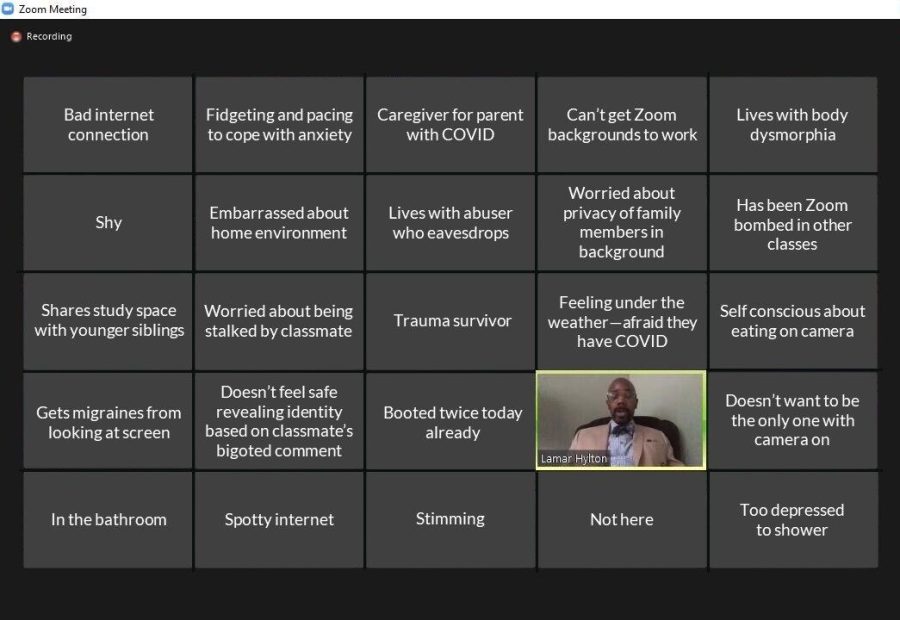

There is a legion of legitimate reasons students might want to keep their cameras off, far too many to list here. One important factor, income level, affects access to private study spaces and stable internet.

Federal Pell Grant receipts from 2016 indicate 32 percent of Kent State students are low-income. Apply that statistic to a class of 30, and 10 students would fall into the low-income category — 10 students who are potentially contending with slow or spotty internet or living in small quarters with many housemates. For students with anxiety about whether their home environment looks presentable, pressuring them to give classmates a glimpse of where they live may have adverse psychological effects. They also may experience video classism — that is the tendency to judge a person based on their home environment.

Let’s remember also that race and socioeconomic status are intimately intertwined. Because non-white people throughout American history did not have equal access to opportunities that would enable them to build generational wealth, a cameras-on policy is more likely to negatively impact BIPOC students — 14.5 percent of Kent State’s undergraduate student body.

It is worth noting that Catherine Prendergast, an English professor at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, reported that when given the choice, her white students typically turned their cameras on while her Black students left them off.

“White students have the assurance that the way [they appear on camera] will be met with approval … but Black students don’t have that privilege,” another user pointed out.

When research indicates experiencing racial discrimination consistently leads to poor academic performance and mental health outcomes, BIPOC students especially should be able to choose if they feel safe enough to turn on their cameras.

Let’s say that, defying statistical odds, all of the students in a class come from middle-class families. They may still live with mental disorders or disabilities that make it difficult to learn with a camera on. Trauma survivors and students living with body dysmorphia may experience extreme distress because video conferencing is so similar to looking in a mirror. Some students, including those who have autism or ADHD, may lack the executive functioning skills to maintain a tidy environment and fear they will be judged if it’s caught on camera. Mandating camera use may trigger anxiety in students on top of the increased stress the pandemic has caused. Disabled or chronically ill students may feel well enough to listen to a lecture but lack the stamina to appear on camera week after week.

Apart from health, some students may have privacy concerns about living with abusers who eavesdrop, living with undocumented immigrants who don’t want to be caught on camera or being stalked by a classmate.

These concerns are not overblown, mostly because Zoom-bombing — a phenomenon where outsiders disrupt a meeting and take screenshots of non-consenting participants — remains a persistent issue. A researcher at Boston University uncovered more than 400 4chan threads and 12,000 tweets sent between December 2019 and July 2020 inviting trolls to Zoom-bomb a class or meeting.

“Students in the class are bored or want to piss off their lecturer or whatever, so they basically post details of their own classes online,” said the researcher, who believes these cases represent a small portion of Zoom meetings targeted.

Does the potential harm that could come to students as a result of turning on their cameras truly justify the potential benefits? Keep in mind using a camera doesn’t automatically guarantee a student is paying attention. And a student who is feeling fearful, anxious or judged because of their race, socioeconomic status or disability is probably not going to experience the sense of connectedness their professor hopes they will.

If a professor is truly student-centered, wouldn’t they want to err on the side of caution and let students decide for themselves if they want to appear on camera? Students aren’t obligated to disclose their struggles to professors, but it is irresponsible to assume students are free of them.

Professors seeking to encourage camera use without putting students in potentially harmful situations can try a number of approaches such as:

-

Invite students to develop and vote on their own camera policies. The rationale is when students create a rule they are more likely to abide by it.

-

Be honest with students about how lecturing to blank squares inhibits your ability to teach. One professor told his students he noticed when two-thirds or more of his students had their cameras off, his teaching suffered. He explained that students deserved to know, so they could make an informed choice about their camera use.

-

Explain how you believe students will benefit from turning on their cameras in your class, specifically. Will camera use directly affect objectives and outcomes?

-

Recognize that you don’t always have to see a person’s face to get to know them. (Facebook groups and subreddits are popular for a reason!) Could giving students a sense of community be accomplished by other means, such as using collaborative workspaces like Google Docs, Padlet or Jamboard?

-

Prompt students to indicate they’re engaged by other means — participating in the chat, answering polls, annotating a slide or responding to inquiries using reactions buttons (thumbs up, heart, applause, etc.)

-

Encourage students to turn on their cameras if their context allows while normalizing the privacy and accessibility concerns that would lead students to keep their cameras off.

Sure, the phrase “Flashes take care of Flashes” has a nice ring to it, but those are just empty words if harmful and discriminatory rules aren’t challenged and changed. Every Flash deserves to feel safe in their pursuit of an education, and the unsung heroes are the professors who affirm it not only with their words but their policies.

Lyndsey Brennan is an opinion writer. Contact her at [email protected].