Opinion: Analysis of ‘Get Out’

March 28, 2017

Over spring break, I went out on a date night with my fiancee and saw the new Jordan Peele movie, “Get Out.”

As a matter of movie review, the music was well selected, the script was strong, the acting was solid and even the comedy spliced in — despite being a horror flick — was pretty good and didn’t feel too out of place.

If you’re on the fence on whether or not this flick is worth the money to be seen in the theater or not, it’s worth every dollar and then some. It’s also a great movie for a date night, too, so there is that.

However, this isn’t a popcorn flick if you pay attention to the undertones and cultural commentary within the movie.

The plot is where the film shines, but it is tinged with unnecessary controversy right now. If you’re worried that it’s a heavy “social justice warrior” piece, it really isn’t. You’d have to project that ideological view onto the movie, or read into the film to dismiss the race questions it brings up.

So, without getting into spoilers, the movie is a horror flick framed from the perspective of a black man who is visiting his white girlfriend’s family home for a weekend. The horror part comes in as there is something — well, off — about the family around whom the movie unfolds.

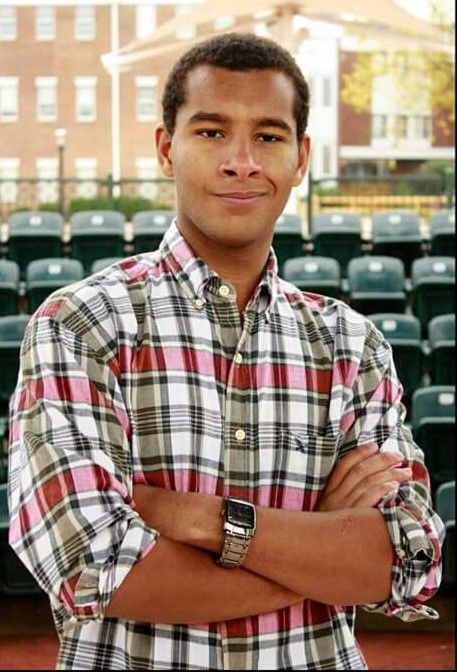

As a black man who is about to marry into a small-town, white family from the mid-Ohio area, I am actually in a special place to comment on the movie, namely in how at the opening — but throughout the movie, also — a large part of the horror atmosphere is created by the anxiety of the black man being brought to meet the white parents and family. An atmosphere of dread is created out of, not just the standard horror tropes, but from the fear of possible racism in the people the main character is set to meet.

Speaking from my own experience in my interracial relationship, I can without shame say this played a part in my real-life anxieties around meeting her parents for the first time. Meeting the ex-marine father alone was enough to be hesitant, but now there was a racial element to the mix.

I called it a “visceral and non-rational fear of white people” because, being black in America, you face enough racism in your time to have rational reasons to be worried around white people.

This movie comments on that lizard-brain kind of fear that you can’t help. It’s not just an “unconscious bias” or an overt prejudice against whites or a strictly rational suspicion of racism; it’s a deep, cloudy and visceral fear.

The movie explores this feeling a little, but it really leaves the question open-ended even by the end.

If we find ourselves experiencing this fear of other races, what do we do with it?

I find that we need to have more interracial dialogue, but it’s definitely an interesting — if not uncomfortable — thing we need to ponder.

Stephen D’Abreau is a columnist, contact him at [email protected].